Tai Chi classes often attract new students because of Tai Chi’s reputation for improving health and well-being. Those interested in staying healthy are drawn to the idea of reducing stress, improving balance and flexibility, sleeping better, and perhaps even managing symptoms of chronic conditions through gentle exercise. Tai Chi is also promoted as “meditation in motion”—though I suspect many people who join classes have never actually tried to meditate before. Understanding meditation in motion is the topic we will explore today.

To start, we need a definition of meditation. Meditation is the practice of training attention and awareness to achieve a mentally clear, emotionally calm, and stable state. Many people picture someone sitting cross-legged in the traditional “Lotus” posture, with eyes closed, hands clasped together, and lost in serene contemplation—something they may not be physically capable of doing. But there are many ways to experience meditation. One that I believe most people have encountered is sitting quietly in prayer before the start of a church service. This time of contemplation could also be described as meditation.

In the late 1960s, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi introduced his Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique to the West. He became a pop culture phenomenon through his association with the Beatles. In the early 1970s, I became interested in meditation, saw an advertisement for TM in our local newspaper, and signed up for the class. The technique involved sitting quietly in a chair with eyes closed and hands together while silently repeating a simple mantra for 15–20 minutes a day. On the very first day of my initiation into TM, meditating with the instructor, I experienced a profoundly deep relaxation and sensation of well-being. In other words, I felt fantastic. Afterwards, I meditated regularly as instructed, and though I felt good, I never quite had the same depth of experience as on that first time again.

A few years later, I started taking Tai Chi classes. For perhaps the first year, I didn’t notice any special relaxation effects. But as time went on, I found that each time I practiced the form, I entered a profoundly calm state. Unlike TM, the relaxation response from Tai Chi was a repeatable experience. At the time, however, I didn’t associate Tai Chi with meditation.

About 15 years ago, while reading the chapter on Tai Chi in the book Asian Fighting Arts by Donn Draeger and Robert Smith, I found a quote that read:

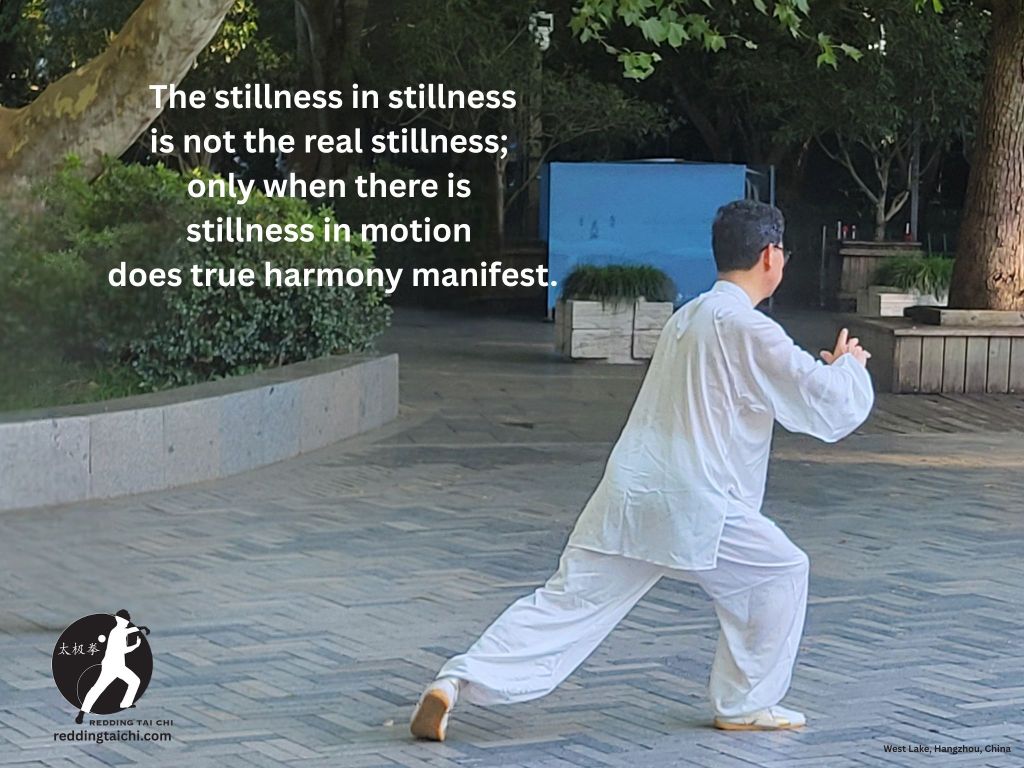

The stillness in stillness is not the real stillness; only when there is stillness in motion does the universal rhythm manifest itself.

It was then I realized that TM (or sitting meditation in general) was the “stillness in stillness” — sitting quietly with a mantra — and that Tai Chi was “stillness in motion” — movement and breathing harmoniously working together to calm the mind and body.

Why Tai Chi Produces a Repeatable Calming Effect Compared to Sitting Meditation

1. Movement Anchors Your Attention

In sitting meditation, you silently repeat a mantra and allow the mind to settle. But your thoughts can drift, and a session might feel less “deep.”

In Tai Chi, the body moves through precise, flowing sequences. The movements act as a built-in anchor for your attention—if your mind wanders, you notice it in your posture or timing and naturally return to focus.

2. Rhythmic Motion Regulates the Nervous System

In sitting meditation, remaining in one position for too long can cause discomfort in the legs, hips, or back—hardly ideal for relaxation. In Tai Chi, slow, continuous rising and sinking movements coordinate with the breath, sending steady “safety” signals to the autonomic nervous system. This activates the parasympathetic branch—the “rest and digest” mode—reducing heart rate, lowering blood pressure, and easing muscle tension. Because the pace and motions are consistent, the calming effect is reliably reproducible—like pressing the same set of buttons each time.

3. Whole-Body Engagement Promotes Physical Release

Sitting meditation is primarily mental; the body stays still, so tension may remain, or be created, unless you deliberately relax.

Tai Chi incorporates gentle range-of-motion movements and weight shifting, which relax the muscles, fascia, and connective tissue.

That release is tangible—you feel your shoulders drop, your breathing deepen, and your face soften, reinforcing mental calm.

4. Breathing Is Built-In, Not Optional

In sitting meditation, breathing is uncoached and natural—fine for some, but others breathe shallowly when sitting still.

In Tai Chi, rising and sinking naturally synchronize the breath without force.

Slow, even breathing sends a direct calming signal to the brain, boosting the consistency of the effect.

5. Posture and Energy Flow

Tai Chi’s upright, open posture promotes circulation and oxygenation, supporting both alertness and relaxation.

From a Western physiological view, what Tai Chi calls qi flow corresponds to efficient circulation within the body.

This upright, flowing form often leaves you calm yet lightly energized—more consistent than the deep, sometimes drowsy stillness of sitting meditation.

In the end:

While sitting meditation and Tai Chi are different, I’ve found they complement each other beautifully. Practicing both seems to heighten the overall effect. But if I had to choose only one, Tai Chi always wins for two reasons: first, it gives me that repeatable ‘stillness in motion‘ where, for me, true harmony manifests; and second, it is highly portable. You can practice Tai Chi anywhere, at any time—no special clothing or equipment needed.

Leave a comment